Albert Chong Hears Trumpets and a Choir

Artist Profile of the Jamaican Photographer for DARIA Art Magazine

Interviewing Albert Chong for DARIA Art Magazine, I revisited my interest in Caribbean cultural production, which I delved into as a graduate student writing my dissertation on Caribbean and African American novels. Chong reminded and re-educated me about the complex cultural and ethnic hybridities in the West Indies and how he approaches these ideas in his art. However, before we pigeonhole him as a Black-Chinese-Jamaican artist, Chong would like us to consider his work and aesthetic separate from the many politically charged identities we want to impose on him.

Here’s an excerpt from the article

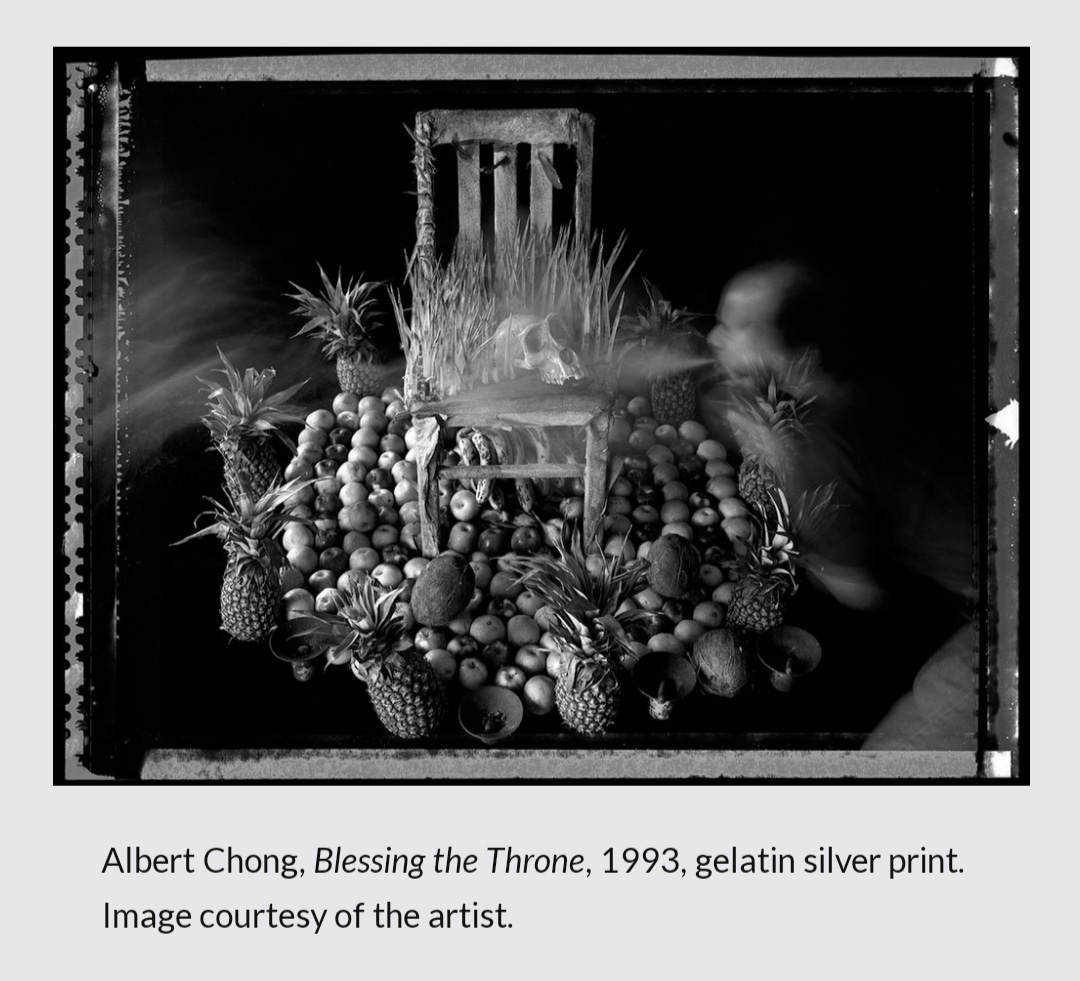

Albert Chong is perhaps the most acclaimed photography, installation, and sculpture artist in Colorado who you’ve never heard of. His long and illustrious career includes pieces that he hopes, as his artist statement proclaims, “[give] expression to [his] human visual intuition, [operating] at levels inhospitable to verbal or literary expression.”

After talking with him, I translated this statement to mean that his art critiques and questions what lies beyond a textual world that codifies bodies with social identities. As a social construction, markers of identity—such as race—are fictions. Yet such historically cemented, often-repeated fictions hold the authority to shape how we see ourselves and others.

Regarding the art world, the language of identity politics establishes a false expectation that all art by artists of color must address these politics while elucidating experiences of social marginalization. Refuting this reckoning, Chong strives to tap into loftier strata of aesthetics, taking us away from denigrated understandings of our existence founded on powerful social hierarchies expressed by and through language.

Chong claims his interest in photography began as a fluke. As a high school student in Kingston, Jamaica, he escaped the brutal heat following sports practice in the air-conditioned darkroom maintained by the Photography Club. As soon as he witnessed prints developing, he “heard trumpets and a choir.” Chong reflects, “If I could imagine an image and see it in my head, I could put it on film. I saw how quick it was—this possibility for image-making.”

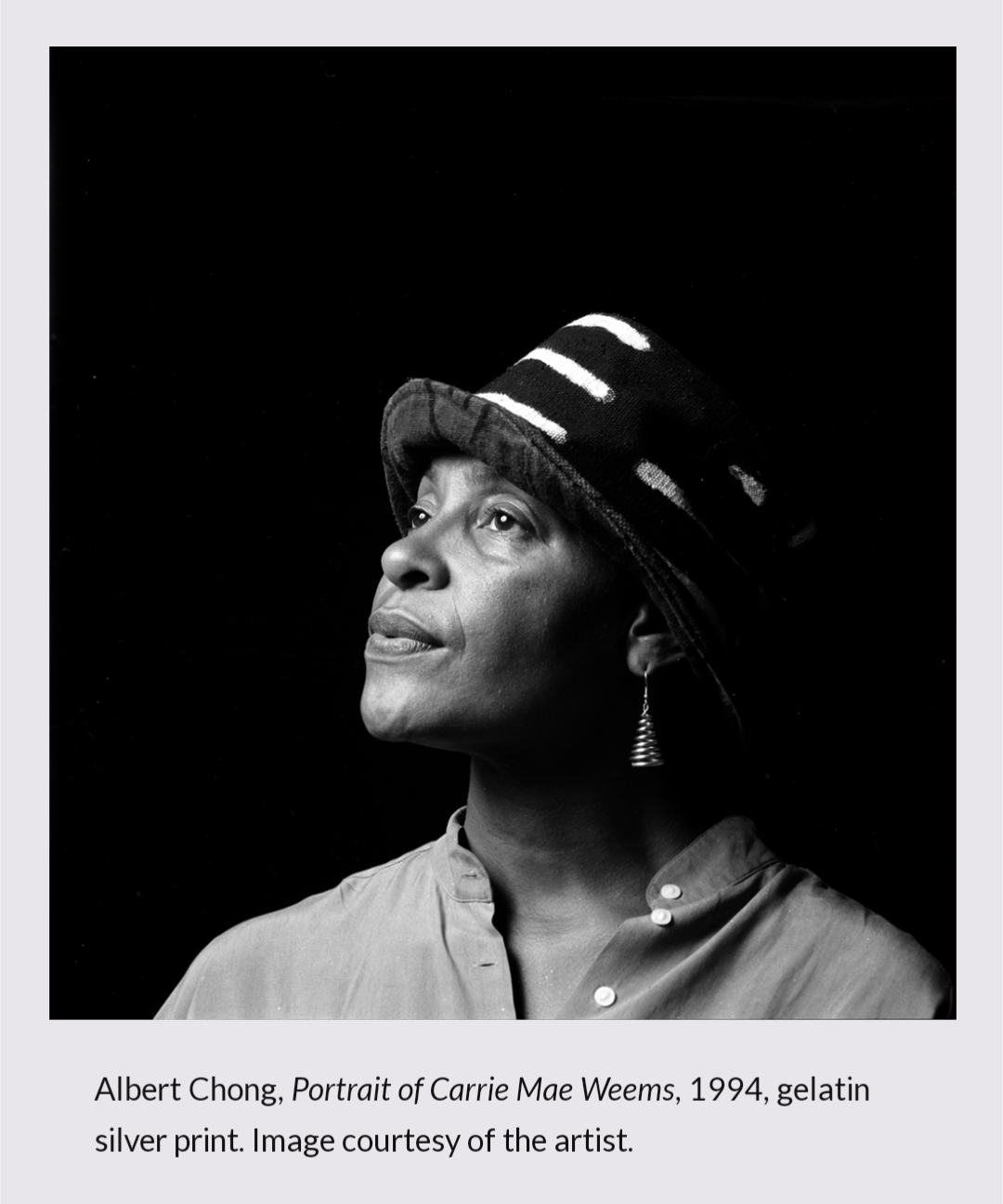

We also discuss his often-overlooked Jamaican portraits, taken in the mid-nineties in Bamboo—a community on the northern coast of the island—with a large format, four-by-five view camera. He used type 55 negative/positive film, developing the negatives on the spot and giving the pictures to his subjects. “Ultimately, these portraits look like documentary-type photographs because my subjects are rural Jamaicans with no embellishment,” he says. However, Chong also reveals that he wanted to present these people “in a dignified way.”

“A lot of these people didn’t have images of themselves,” Chong explains, “And when I took their photographs, I told them, ‘I want you to think about how you want to be seen in the future.’”

For his own future, Chong wants more time to work on his family’s remote Jamaican farm, acquired in 1968. Chong fondly recalls visiting the place as a child, getting out of hectic Kingston to raise pigs and tend crops that would later be sold in the city. After his father’s death in 1989, the family neglected the land until 2013, at which point Chong returned every summer to renovate and build on it.

“It’s difficult for artists to retire,” Chong laments. “My continuing exhibition schedule prevents me from living in Jamaica full-time.” Hence, for the time being, Chong stays put in Colorado for most of the year, where he remains overlooked. Yet, hopefully, he finds some consolation in his assured position in the annals of art history.

Read the full article here.