Taking Time with “Mutual Terrain” at the RedLine Contemporary Art Center

And Making Haste to See It as It Closes this Weekend

Curated by local Denver video artists Adán de la Garza and Jenna Maurice, who run Month of Video, the exhibition Mutual Terrain at Denver’s RedLine Contemporary Art Center presents global artists’ interactions with various landscapes. (ICYMI I wrote about the first year of Month of Video here.) These videos explore how terrains shape individual and collective perceptions of self, place, history, and time.

De la Garza and Maurice also have a history of interacting with land in their respective artworks. In Maurice’s series “Concerning the Landscape: A Study in Relationships,” she buries her head into the scorched earth at Death Valley, hugs a cactus in Arizona, and vomits off the side of Niagara Falls. Through these pieces, Maurice attempts to learn nature’s language and find pathways to empathy and alternative ways of existence. (ICYMI I also wrote about her and her artwork here.)

De la Garza underlines more overtly political themes in his videos, such as “Protest Etiquette,” where he balances a Molotov cocktail on his head while walking across The Devil’s Golf Course in Death Valley. In this piece, he comments on the “the ‘centrist’ cry for civility” that occurs when people protest injustice and state violence. He also runs Collective Misnomer, an artist collective “exhibiting contemporary time-based art (sound, video, performance)” at various venues across Denver.

Considering Maurice and De la Garza’s separate bodies of work, Mutual Terrain builds on conversations about how and why video artists focus on landscapes, finding it necessary to deconstruct art’s conventionally colonial gaze.

Felix Kalmenson’s “A Line Is Not a Line” considers this issue through low-resolution satellite imagery of contested social-political territories with fictitious but authoritative borders.

In a similar vein, Rick Silva’s “Western Fronts: Cascade Siskiyou, Gold Butte, Grand Staircase-Escalante, and Bears Ears” alerts us to endangered US monuments that are losing government protections. Silva underlines this precariousness by reducing sections of drone footage of the monuments to grayscale polygons.

Other works are more personal. Nina Kurtela’s “Dear Aki,” a visual-narrative letter to the Finnish film director Aki Kaurismäki, constructs “fictional space” as she performs how her Croatian identity overlaps with Finnish identity.

The remaining videos include Nika Kaiser’s abstract view of US swamps in “Soft Slough,” Ali Cherri’s “The Digger,” documenting the stewardship of a United Arab Emirates’s neolithic burial site with no human remains, and Ella Morton’s examination of Newfoundland indigeneity in “The Great Kind Mystery.”

You encounter Kaiser’s “Soft Slough” first as you enter the gallery. It is the only video to be sectioned off in an alcove, and it is also the most interactive. Below a projection of wetlands shot in Louisiana and Arizona, a pool-like half-circle mirror on the ground shows the images right-side up, creating a kaleidoscopic effect. The mirror also invites viewers to insert themselves into the piece when they stand close enough to see their reflections staring back at them.

Another screen on a box television perches in front of the display. Cutting to images of alligators with their heads breaching the surface of the water, the simultaneously playing videos also include environmental activists submerged in water with only their eyes visible, mirroring alligator-like behavior.

In this way, Kaiser gives us a glimpse into the “murky depths of interconnectedness” between humans, other animals, and their habitats. While the specific ecosystem Kaiser films has sheltered alligators for tens of millions of years, Kaiser also notes that the swamp has harbored US maroons—enslaved Black people who liberated themselves, establishing their own communities, culture, and forms of governance within but beyond the surveillance and brutality of the ethno-state that sought their recapture.

This sometimes foreboding place of opaque water, dense vegetation, and curtains of moss—as well as the riotous noise of its various inhabitants, given to us in a crescendoing soundtrack—is presented from a different angle—as the setting of a haven as opposed to a Gothic horror. In “Soft Slough,” the swamp becomes a space of possibility, where we confront marginalized histories, human and otherwise, that decenter the eurocentric primacy of Man. Through this destabilization, human-nature inextricability and pursuits of freedom are reimagined.

The sounds of the swamp continue to break into the viewing experience of Cherri’s “The Digger,” the second video to appear as you enter the gallery. Its more subtle soundtrack rains down from an overhead directional speaker. As the frenzied pitch of Kaiser’s US swamplands overtake images of Sultan Zeib Khan, moving through the “Neolithic necropolis in the Sharjah desert” that he has cared for through two decades, we are asked to think about what, if anything, connects these two separate terrains and situations. Recalling Kaiser’s “murky depths of interconnectedness,” the exhibition as a whole plays on this idea as the videos’ soundtracks overlap.

Since most of the videos are played on a loop, you’re likely to encounter a piece somewhere in the middle of its narrative. Watching Khan is his white robe midway through various tasks—digging into the ground, carrying a lantern through a darkened desert, and meditatively circling beehive-like stone domes that camouflage with the taupe earth—it is not immediately obvious that he attends to a burial site, or, as Cherri describes it, keeping a ruin “from falling into ruin.” His lonely, Sisyphean dedication becomes amplified once we learn by the video’s conclusion that the land has been purged of the human remains that were excavated for display in a museum.

If you catch the video from the beginning, too, Cherri notes that this “grave [has become] a grave.” Without this context, though, Khan appears to be on a mysterious spiritual journey, displaced from time and modernity, with only hints of the contemporary setting haunting the distant background as an urban cityscape faintly breaks through the haze on the horizon. In one poignant scene where past and present collide, a camel is spotlighted by the headlights of passing cars while music blares in spurts from radios.

By the end of the video, we see the museum displays of this gravesite, with placards that read “Honoring the Dead” visible in the background. Through this conclusion, Cherri considers the contexts in which we honor the dead as well as what happens to them when their bones become historical artefacts.

Perhaps one way that “Soft Slough” and “The Digger” speak to one another—and how all of the videos speak to one another—is through a shared inquiry into time, which often exists in our consciousness as a binary between time before humans and time after them. In traditional studies of Western art, time has also been formally stylized as time before Christ and the time after his death—a time that holds no significance in the swamp and a different significance in Muslim-dominated areas.

As these videos demonstrate, the terrain ceaselessly produces time, regardless of human presence. Earth also undermines the time of rising and falling human civilizations as its rocks and prehistoric flora and fauna provide evidence that the terrain has been here long before us and will be here long after.

On the other side of the partition from “The Digger,” the remaining four videos in the exhibition face each other. Morton’s “The Great Kind Mystery” presents distorted Super 8 and 16mm footage of Newfoundland landscapes. Over these images, Amy Hull, an Inuk and Mi’kmaw woman, narrates her memories of growing up on the island.

Adding to considerations of time in relation to landscape, Hull notes how the sight of rocks and trees makes her aware of death and transforms concepts of what it means to age in a non-human sense.

Hull also discusses the comfort she finds in feeling small and insignificant in the face of nature—the “great kind mystery” from which we all emerge. “She owns you,” Hull observes about nature, suggesting that it has never been the other way around. Perhaps submitting to nature’s power, Hull implies, is the only way to find peace, and maybe even liberation.

Much of “The Great Kind Mystery” is concerned with what it means to be “indigenous” to a piece of land, too. Hull complicates more than illuminates this issue as she discusses her hybrid European and non-European roots—an inevitable convolution following a genealogy spawned from colonial contact.

Kurtela’s adjacent “Dear Aki” also thinks about where one is from and how one’s spatial origins shape a sense of self, influencing the direction one’s life takes. Although Croatian, Kurtela unravels a curiosity about becoming Finnish, explaining that her Finnish-sounding surname often leads people to assume she is Finnish. “Can I become Finnish?” Kurtela asks in a letter to Aki, acknowledging that identity is a performance.

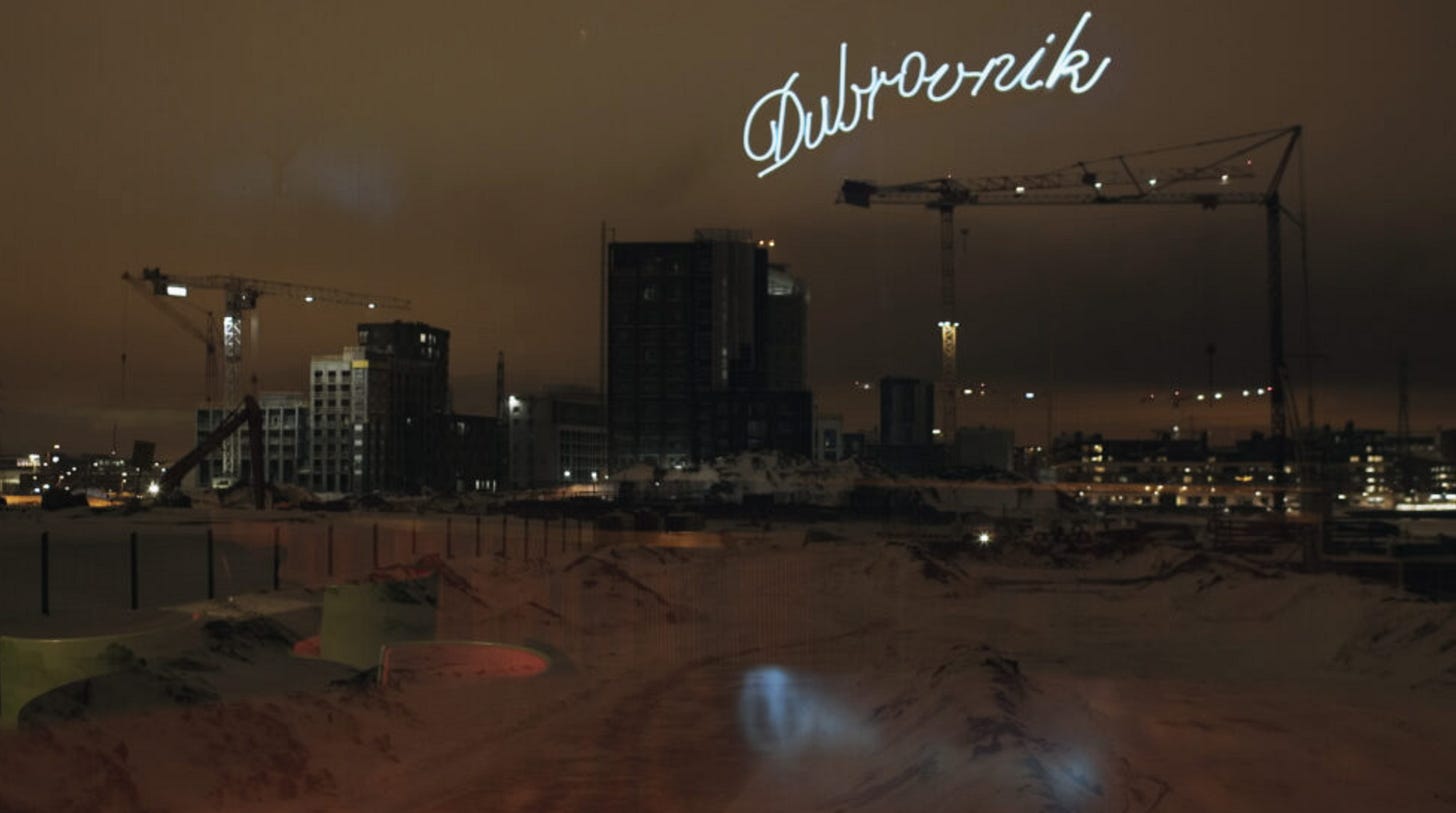

“[Juxtaposing] northern and southern imagery”—atmospheric images of snow, ferns, water, and sky—Kurtela disorients viewers, making them unsure if they are in Finland, Croatia, or somewhere else. She also creates a Helsinki sign, a replica of a sign she saw in Aki’s film Drifting Clouds, in which a bar in Helsinki contains a neon sign that reads “Dubrovnik.” Placing her sign in various spots in Dubrovnik, the confusion she inspires in her audience also replicates the confusion Aki created for her in Drifting Clouds.

Experimenting with creating fictional spaces in “real” spaces by calling Dubrovnik Helsinki, Kurtela highlights the power the act of naming has in shaping our notions of self and place.

Silva and Kalmenson’s respective pieces take us out of the personal and into the more general and theoretical terrain of political landscapes, as the lands depicted in these videos are directly impacted by state surveillance and policing.

“A Line is Not a Line,” Kalmenson explains, “examines the practice of landscape visualization as a technology of colonialism.” Connecting Google Street View to the colonial mapping executed through traditional landscape paintings, Kalmenson insists that the colonial gaze is not a historical and dead ideology. In fact, this gaze and the act of cartography continue to do violence, which can be traced and documented through maps, digital or analog.

Silva’s “Western Fronts” thinks about shrinking borders as US western monuments grow vulnerable under the Department of the Interior’s relinquishing of land protections in areas that also exist as sacred sites for Native American communities. As a result, oil, gas, and uranium mining companies have already encroached on some of these lands.

The colonial gaze and projects of Western Expansion, as Silva and Kalmenson’s videos together underline, continue to proliferate the exploitation of both people and landscapes.

While Mutual Terrain dissects many important contemporary themes relating to land and landscape art, it also teaches us how to view video art. In the absence of static objects, the only way we can engage with each film is by watching it until it loops back to the place where we started. You thus have to take your time with the pieces since videos, unlike paintings, must be watched for their full duration.

In more ways than one, Mutual Terrain links spatiality with temporality. On the one hand, visual projections that require time to digest occupy space in a darkened gallery differently from well-lit installations, sculptures, and art on flattened canvases. On the other hand, these works also probe philosophical questions about how the past, present, and future are embedded in the natural world we inhabit.

And you’re running out of time to see this exhibition that brings together deep meditations on time, artistic mediums, and landscape—it wraps up on August 3rd.